Nothing makes a naturalist happier than catching an animal unawares

By Richard Hoath

I spent the festive season in England. After the inevitable excesses of Christmas and the New Year, there was time before returning to Cairo for a true wind down, which in my case means long walks over the muddy and very, very wet English countryside with the family Labrador, Lottie. Flocks of winter thrushes — Redwings and Fieldfares — and parties of tits, nuthatches and chats foraging busily through the boughs were our reward. And after the walk, the pleasant sensation of warming up on the sofa with a hot drink and a wildlife DVD.

And the Labrador joined. Not officially allowed on the sofa, a truce was made over the holidays and there I was with a hugely content and comfortable snoozing yellow Labrador curled up on the settee. Much like Mr. Obama and Mr. Clegg at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service a couple of months ago, I could not resist a selfie with the blonde, In their case, much to the apparent chagrin of Mrs. Obama ,that blonde was the Danish Prime Minister. My selfie, a snoozing Labrador along with my feet, went viral — though a very limited viral within the Hoath household.

In my other life as a university lecturer, I am of course used to people falling asleep in my presence or rather in the face of my oratory. In my far-flung campus beyond Katameya, I choose to teach early classes largely so that if (some may argue when) the students fall asleep I can indulge in self-delusion and persuade myself that it is not my speaking skills but the obscenely early hour that is to blame.

But there is something very heartwarming when an animal is so comfortable in your presence that it falls asleep. And that is compounded many-fold when that is a wild animal. Animals, and especially mammals, are often extremely difficult to observe in the field, in the wild. That is scarcely surprising – many are potential prey for other species and even the predators rely largely on not being detected in order to predate successfully. But I have on occasions been privileged enough to have truly wild animals, and most memorably mammals, fall asleep in front of me. It is a curiously moving experience.

The first memorable experience was in Morocco. I was there to climb Mount Toubkal, the highest point in North Africa, which naturally involved trekking in the High Atlas. I had numerous bird species on my wish list including the Crimson-winged Finch, Barbary Partridge and Moussier’s Redstart, but my real aim was North Africa’s only primate, the Barbary Macaque also known, incorrectly, as the Barbary Ape. From the small town of Azrou near Meknes, I trekked in the pine- and oak-clad foothills. I had little luck until late one afternoon, heady with forest scents and sounds, I scanned a row of crags across a gorge from me. And the top of the crags moved. I had found my macaques.

It was too late get closer that evening, but the following morning I returned, and after traversing the rock-strewn forested slopes I had found little save a covey of Barbary Partridges that had erupted from below my feet, and a fledging European Nightjar along with a very defensive mother. The monkeys had seemingly moved on. And then slowly I became aware of crashing in the trees above. Very soon I found myself in the midst of a troop of the macaques I had come so far to find. Macaque society, like most primate societies, is highly social and interactive but of particular interest is the use of infants in reducing tensions between older animals. I sat down in the forest and just watched and noted and sketched.

I soon became aware that the macaques were not the only ones being watched. One, seemingly the largest of the troop, presumably an adult male, had taken up a position on a large rock just a few meters away from me. As he watched me I watched him and thus was able to make more prolonged and accurate sketches than I had ever been able to make of a wild animal. And as I sketched, his eyelids drooped, his body sagged and before long I had an adult Barbary Macaque in front of me fast asleep. The honor! The privilege!

Fast forward not very far to Malawi, not the town in Middle Egypt, but the country in southern Africa. I was in the Lengwe National Park south of Lake Malawi on the Shire River. The landscape was incredibly lush and verdant and as green as a Fayoum berseem field. Bordering the river were extensive grasslands scattered with patches of acacia and dotted with towering termite mounds. As I was hiking through this riparian savannah, a striking profile caught my eye. Atop one of the termite hills was a magnificent male Bushbuck — chestnut above with narrow white stripes down the flanks and with a fine pair of rather heavy, barely spiraled horns. Were I of another era and another mindset, a mindset I simply cannot comprehend, a fine trophy. My aim was much simpler and infinitely more challenging. I was downwind of the buck and he had not scented me yet, nor indeed seen or heard me. I could get much closer.

A trek through the bush revealed Böhm’s Bee-eater and a magnificent Levaillant’s Cuckoo but for once the birds could wait their turn. After long and circuitous circling I found myself in a clearing. In front of me was the Bushbuck half hidden behind the red earth of the termite mound but with his flanks showing and so close that I could see them rise and fall with his breath. I got closer and closer, barely able to breath myself until I was almost within petting distance of a wild antelope. And then the air exploded. Perhaps a crushed twig. Perhaps my scent. Perhaps a warning call from one of the very aptly named Go-away Birds or Grey Louries. In a blur of chestnut, the buck erupted out into the bush leaving me just a nano-second to whip out the camera and take a shot as he charged past me. It is a blur but the picture has such frisson that it is still one of my favorites.

Unbelievably I had a similar encounter here in Egypt with a pair of Dorcas Gazelles in the northern Eastern Desert. The scenario was much the same: A distant glimpse followed by a protracted and circuitous stalk and then the final reward of the brace, a male and a female glimpsed from cliffs overlooking a wadi floor. They were feeding, the female the more active of the two grazing on desert shrubbery. The male, larger and with much thicker and more heavily ringed horns, lying on the ground and chewing. Again for a short time while they were totally unaware of my presence I had them to myself — not asleep but completely unaware of my presence. And again, whether it was the rustle of note paper, the shuffle of clothing or the imperceptible waft of scent they were up and gone, leaving just a wonderful memory. O and droppings that I, ever the naturalist, collected.

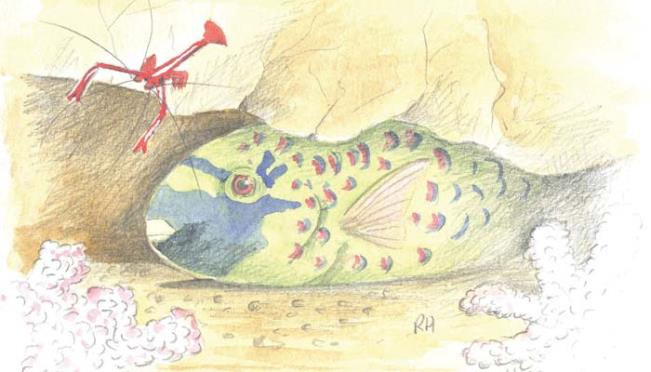

Not everyone is going to have these experiences. I count myself extremely lucky and privileged to have indeed been privy to them. But such encounters are not necessarily always as elusive. For those that dive, an audience with a sleeping parrotfish is something to experience at night.

By day, parrotfish are some of the most obvious of the coral reef inhabitants, large and often brilliantly hued in turquoises, oranges, pinks, greens and myriad other shades. They feed by scraping algae off the corals using the parrot-like “beak” that gives them their name. By night they sleep in crevices and crannies in the reef and further protect themselves from predators by enveloping themselves in a mucous duvet of their own making. This not only makes them unpalatable to predators but, perhaps because the sticky substrate ensnares zooplankton, means that they are often attended by gaudy crimson and white cleaner shrimps. Sleeping beauty indeed. et

Comments

Leave a Comment