An invaluable natural resource is under threat from pollution

By Richard Hoath

It seems that 2014 ended if not with a bang then with a crash. The crash in question involved two vessels, one a tanker transporting 350,000 liters of oil, and took place in the vast maze of waterways, channels and wetlands that makes up much of the Ganges Delta in Bangladesh. The region, known as the Sundarbans, is the world’s largest mangrove forest, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and it supports a host of incredible and incredibly rare species.

The Sundarbans are perhaps most famous for their population of Tigers, a population numbered in the 100s and perhaps the largest remaining contiguous population of this critically endangered big cat on the planet. Also present is the enigmatic Fishing Cat, a felid that does exactly what its name implies and is not much larger than our domestic moggy that is famous for its aversion to water. Also occurring is a rare monkey, the Capped Langur.

But it is the aquatic species that are most at threat from the slick emanating from the stricken vessel. The Sundarbans is home to the world’s largest crocodile, the Estuarine or Salt-water Crocodile, and supports populations of two species of otter, the Smooth-coated and Oriental Small-clawed. Endangered sea turtles — including Hawksbill, Olive Ridley and Green — breed on the sandbanks.

Perhaps of most concern are two small but critically endangered cetaceans. The Ganges River Dolphin has a global population of possibly just hundreds. This effectively blind, slender-snouted species echo-locates for prey in the murky waters of the Ganges and is threatened by pollution, hunting, over-fishing and dam construction. An oil slick will just add to its woes. The Irawaddy dolphin has a wider range, but it too is threatened everywhere. The last 60 in Burma’s Irawaddy River face the added threat of electrocution — an innovative ‘fishing’ technique used by Burmese fisherman.

And then of course there are the mangroves themselves. Mangrove trees thrive in shallow, salty or brackish tropical coastal waters and are uniquely adapted to their environment. The mangrove trees tolerate the saline water by filtering out the salt via specially adapted glands in the leaves and roots. They obtain oxygen in the poorly aerated muddy substrate through an elaborate system of stilt roots and through specially adapted pneumatophores, aerial roots that bear more than a passing resemblance to asparagus. They filter out pollutants and recycle nutrients.

Apart from providing habitat for a host of birds and mammals, mangroves are important in providing vital habitat for many fish and invertebrate species and especially young fry and juveniles for which the tangle of roots acts as a natural, protective nursery. The forests also function as a natural barrier stabilizing fragile shorelines from the action of water and wind (and tropical cyclones are not mere zephyrs) and most famously, tsunamis. Commercially, they are a source of livelihood for local people, for timber, for charcoal and nowadays because of the fauna that they support, for tourism. Mangroves are jolly good news.

All this is now threatened as the Bangladeshi authorities try and tackle the slick with insufficient resources, leaving the local people trying to save their livelihoods by scooping up the oil in pots and pans and even sponges.

But this is happening many thousands of miles away, so why my concern for here? Well, Egypt too boasts mangroves, mainly of the White Mangrove Avicennia marina. Stands can be found along the coast of South Sinai, most notably at El Nabq and at Ras Mohamed, and along the Red Sea coast from the islands at the mouth of the Gulf of Suez south to Marsa Alam and beyond. These invaluable habitats are already threatened by rampant coastal construction, tourist development, by tourism itself and by pollution.

In 1996, I took part in a survey of the Red Sea islands mentioned above, focusing on the breeding seabirds. We noted severe pollution particularly on the western shores of the islands, notably Gezira Tawil, plastic as ever being the major culprit but also oil. The northern Red Sea is a major oil-producing region as well as a primary shipping lane, and the combination of industry and marine traffic was having a detrimental effect even back then.

My concern is that the construction and development of the much vaunted second Suez Canal, with all the extra traffic that suggests, will greatly add to the environmental threat to the area. Egypt may not have the Tigers, Fishing Cats, otters and crocodiles of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans, but it has the breeding sea turtles. The dolphin species may not be as critically endangered as the diminutive Ganges River and Irawaddy dolphins, but it has several vulnerable marine species. And the bird life of Egypt’s Red Sea mangroves is spectacular.

A visit to a mangrove swamp is a heady experience. The silt and sludge of the substrate has a distinct aroma and just adds to the sheer incongruity of such a lush green enclave on an otherwise barren coastline. The mud positively fizzes with a zillion Fiddler Crabs, small crabs the male of which has one claw greatly enlarged and often brightly colored. This he uses as a flag, signaling his intentions to any potential mate, and as a weapon in combat with other males over those same females. Also found are ghost crabs, larger and longer-limbed and active predators amongst the rootscape.

Overhead the air is often filled with the harsh and wholly unmusical cries of terns — White-cheeked, Bridled, Lesser Crested, Crested and the biggest and most vociferous of all, Caspian. This, the world’s largest tern, is readily distinguished by its huge carrot of a deep orange bill.

Along the Red Sea, Egypt’s mangroves provide a vital breeding habitat for a number of heron species. Perhaps the most obvious is the Western Reef Heron that builds a flimsy platform of twigs in the trees on which to lay its eggs. This bird is very similar to the Little Egret of the Delta and Valley, all white with dark legs (not the clean back of the Little Egret), yellow feet (though duller than the Little) and a dark bill usually with a yellowish base or tip. Curiously, an all-black egret, relieved only by a white throat, is likely to be the same species as it occurs in two color phases as well as intermediates. It can be very confiding and while nesting in the mangroves it can also be found patrolling, bold as brass, the constructed shallows of El Gouna and other tourist resorts.

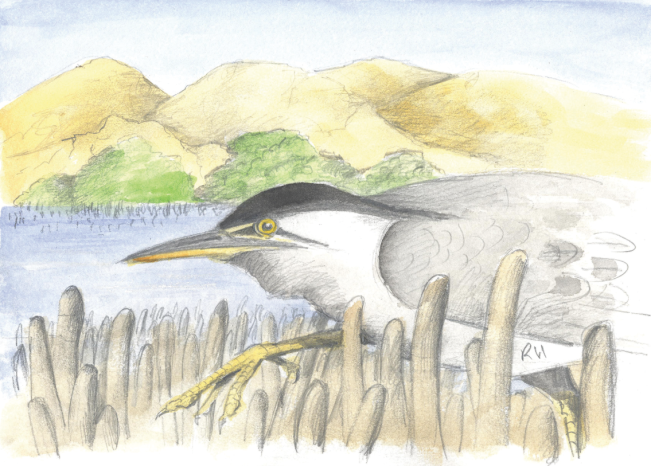

More secretive is the Striated or Green or Mangrove Heron. This thickset heron is largely blue-gray above and below with a black cap, yellow legs and short, sharp bill. It is very unobtrusive amongst the tangles of roots and pneumatophores but seems to be doing well. It is now being recorded regularly not just on the coast but also along the Nile Valley in southern Egypt.

A rarer and more spectacular specialty of the southern mangroves is the stately, spectacularly named Goliath Heron. This aptly labeled giant reaches 150cm in length with a wingspan of well over two meters. I have only seen it once in Egypt, south of Marsa Alam in 2001.

But one does not need to venture to the exotic Red Sea coast for the mangrove experience. There is always the desert southwest of Fayoum. Many will be familiar with Wadi Al-Hitan, the Valley of the Whales, like the Sundarbans a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Here lying out in the sand are the partially excavated fossil skeletons of whales, notably Basilosaurus isis and Dorudon atrox. Their importance lies in the fact that these fossils, dating back some 40 million years, show that these whales had external rear legs and legs with feet and toes — a feature found in no modern whale and that is vital in our understanding of whale evolution. But Wadi Al-Hitan has other fossils, of sea turtles and dugongs and the like. And there is a fossilized mangrove bed, a tangle of roots and pneumatophores frozen and aeons old, yet instantly recognizable.

What has just happened in the Sundarbans should serve as a warning, given the construction and development along the Red Sea. Otherwise these fossils in the Western Desert may yet be the only mangroves left in Egypt.

Comments

Leave a Comment