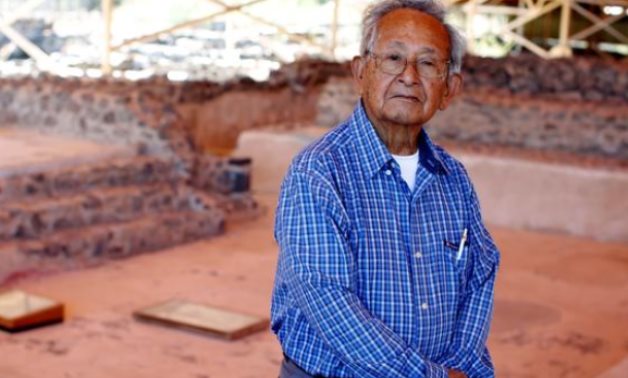

Mexican archeologist Ruben Cabrera, who pioneered excavations at La Ventilla beginning in the 1990s, stands in front of the Patio of the Glyphs - REUTERS/Gustavo Graf

TEOTIHUACAN, Mexico (Reuters) - Among the many mysteries surrounding the ancient Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacan, one has been especially hard to crack: how did its residents use the many signs and symbols found on its murals and ritual sculptures?

The city’s towering pyramids reopened to visitors earlier this month as pandemic restrictions eased. But perhaps its most interesting and extensively-excavated neighborhood, featuring a patio floor with rare painted symbols, or glyphs, remains off-limits to tourists.

The discovery in the 1990s of the puzzling red glyphs, most laid out in neat columns, has led a growing number of scholars to question the long-held view that writing was absent from the city, which thrived from roughly 100 B.C. to 550 A.D.

Their ultimate ambition is to harness the steady drip of new finds to one day mimic the success their peers have had decoding ancient Maya or Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Teotihuacan – which lies in a dusty plain about 30 miles (50 km) outside the modern Mexican capital - was once the largest city in the Americas, home to at least 100,000 people.

Yet much is unknown about the civilization that inhabited it, including what language its native inhabitants spoke and whether they developed a system of writing akin to that of the Aztecs, who dominated the area some eight centuries later and revered its ruins.

Experts have debated several theories for the glyphs. They say they may have been used to represent symbols used to teach writing, or place-names of subjugated tribute-paying cities, or even as signs used in disease-curing rituals.

Art historian Tatiana Valdez, author of a book published this year on the glyphs of Teotihuacan, says the patio’s 42 glyphs, many in linear sequences, amount to the longest text ever found at the city’s ruins.

Overall, she says more than 300 Teotihuacano hieroglyphics have been tentatively identified so far.

Countless ancient Mexican codices - accordion-style folded paper books covered in hieroglyphics - were ordered burned in colonial times by Catholic authorities. Only about a dozen still exist.

Valdez is convinced such books were also part of Teotihuacan’s literary tradition, over a millennium before the bonfires.

“I think Teotihuacan used hieroglyphics, and used them well because we’ve found so many,” she said, pointing to thousands of mostly clay figurines with painted or incised glyphs that have been found on the site.

Valdez said the sheer number of figurines found with glyphs on tiny headdresses or on their foreheads could mean some access to writing was available to commoners.

Walking around La Ventilla, where the glyphs patio is located, is tantamount to exploring an ancient neighborhood, featuring temples, artisan workshops, intricate apartment compounds and finely painted murals.

The government-run National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) said additional work is still needed to be able to open it to tourists, but did not offer any timeline.

The neighborhood’s major excavations were completed years ago.

Comments

Leave a Comment