Living in Egypt intensifies nostalgia for the golden age of travel.

director at AUC Press

At the risk of sounding mildly deranged, I have often considered that I was born a century or so later than I should have been.

As a lifetime student of archaeology, I suppose that it is not too much of a surprise that I have one foot placed firmly in the past, but the feeling has only intensified since I came to live in Egypt. This particular delusion is greatest when I travel to see the great historic sites of the country and try to imagine what they would have been like when they were first seen by foreign travelers. What we see today at Luxor or Deir el-Bahari is a sanitized and reconstructed version of those first perceptions — almost as much cement as stone — which satisfy the needs of modern tourism, but not those of archaeological romanticism.

Fortunately, the camera made an early entry into Egypt, and so we can make some attempt to see the remains of ancient Egypt through the eyes of earlier generations of travelers.

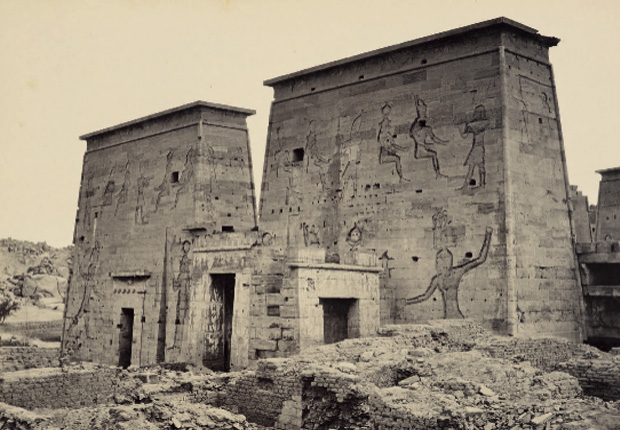

One of the most distinguished of those early photographers was Francis Bedford (1815–99), who had trained originally as a draftsman and lithographer, and maintained his artistic eye for composition in the images he captured. Bedford joined the Prince of Wales’ Near Eastern Tour of 1862 and produced some of the most evocative images of the ancient Egyptian buildings before their full excavation, such as the ones below of the first pylon of the Temple of Isis at Philae, and the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.

The first pylon of the Temple of Isis, Philae, by Francis Bedford, 13 March 1862. From Gordon & El Hage, Cities, Citadels, and Sights of the Near East, AUC Press. (Courtesy HM Queen Elizabeth II)[/caption]

The first pylon of the Temple of Isis, Philae, by Francis Bedford, 13 March 1862. From Gordon & El Hage, Cities, Citadels, and Sights of the Near East, AUC Press. (Courtesy HM Queen Elizabeth II)[/caption]

The Temple of Hathor, Dendera, by Francis Bedford, 19 March 1862. From Gordon & El Hage, Cities, Citadels, and Sights of the Near East, AUC Press. (Courtesy of HM Queen Elizabeth II)[/caption]

The Temple of Hathor, Dendera, by Francis Bedford, 19 March 1862. From Gordon & El Hage, Cities, Citadels, and Sights of the Near East, AUC Press. (Courtesy of HM Queen Elizabeth II)[/caption]

Who wouldn’t want to go scrambling around in those ruins for days on end, given the opportunity?

By our very nature, however, archaeological romantics never think about any of the hardships that might have preceded the taking of these photographs — the interminable journey to Egypt, the challenges of the desert or river, and the equal, if not greater, challenges to the gastrointestinal tract.

For the average traveler, the worst of such hardships began to recede in the years after Thomas Cook brought a party of 30 visitors to Egypt in 1869, hired two steamers from the khedive, and ushered in — somewhat inauspiciously at the beginning — the golden age of travel on the Nile.

Early steamers on the Nile. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Corbis Images)[/caption]

Early steamers on the Nile. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Corbis Images)[/caption]

The idea of the tour group was much derided at the time, the British satirical magazine Punch going so far as to suggest that those going on Cook’s tours must be mental patients. Yet the floodgates gradually opened, if only for the time being for the sufficiently well-heeled, and the first groups, composed of British, French and American travelers, were among the first to be photographed at the base of the Great Pyramid at Giza.

A party of early Cook’s tourists at the pyramids. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Thomas Cook Archives)[/caption]

A party of early Cook’s tourists at the pyramids. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Thomas Cook Archives)[/caption]

Those initial tour group journeys remained quite uncomfortable (in the 1860s it was only possible for Cook to rent ‘converted’ cargo ships from the khedive), but by the 1890s the characteristics of life on a Nile cruise we are familiar with today, including the ritual of chronically pale northern Europeans absorbing the winter sun, were well established.

Thomas Cook passengers in the winter sun, circa 1890. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Andrew Humphreys)[/caption]

Thomas Cook passengers in the winter sun, circa 1890. From Humphreys, On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Andrew Humphreys)[/caption]

As travel to Egypt developed over the following decades, attracting the likes of Florence Nightingale, Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie, so too did the watering holes at the principal waypoints, Alexandria, Cairo, Luxor and Aswan. The grand hotels — Shepheard’s (where Cook’s had their office), Semiramis, Mena House, Winter Palace, Cataract and Cecil — offered the last word in luxury and were, essentially, European outposts planted in the Egyptian heat, dust and apparent chaos (though I would like to think that only a few would entirely share the sentiments of a Mr. Ellis of Boston, who wrote in the Shepheard’s guestbook in 1858: “Dreadful country, wonderful pyramids, and excellent hotel!”)

The Grand Terrace at The Cataract, Aswan. From Humphreys, Grand Hotels of Egypt, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Corbis Images)[/caption]

The Grand Terrace at The Cataract, Aswan. From Humphreys, Grand Hotels of Egypt, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Corbis Images)[/caption]

So extravagant did the hotels in Cairo become that the New York Herald predicted in March 1883 that Cairo would eclipse both Nice and Naples and become the most fashionable winter resort in the world.

The Hotel Cecil, Alexandria, in the 1930s. From Humphreys, Grand Hotels of Egypt, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Mohamed El Mekabbaty)[/caption]

The Hotel Cecil, Alexandria, in the 1930s. From Humphreys, Grand Hotels of Egypt, AUC Press. (Courtesy of Mohamed El Mekabbaty)[/caption]

What an era that must have been to have visited Egypt for the first time! To have seen the ruins of ancient Egyptian temples still half-buried in the sands; to travel along the Nile when it was still an adventure to do so (as late as 1849 crocodiles could be seen as far north as Minya); and to rest one’s head in the most elegant surroundings to be found anywhere in the world at the close of day.

I hope these words and images help explain my mild derangement, but, if you are not fully convinced, let me end by borrowing someone else’s words as final evidence of the romance of the golden age of Egyptian travel:

“The sailing on the moon-lit Nile has an inexpressible charm; every sight is softened, every sound is musical, every air breathes balm. The pyramids, silvered by the moon, tower over the dark palms, and the broken ridges of the Arabian hills stand clearly out from the star-spangled sky.” (Eliot Warburton, 1843, from A Nile Anthology, AUC Press).

Join Nigel Fletcher-Jones on Facebook. To find your closest AUC Press Bookstore, browse their list of stores.

Comments

Leave a Comment