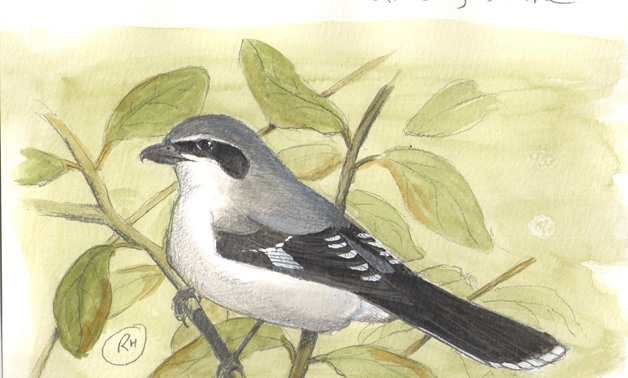

Great Grey Shrike by Richard Hoath

There can be little doubt of the book so far in 2018. I am two-thirds through "Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House" by Michael Wolff, which I find rather disappointing. This is not sour grapes, because it has already outsold my own Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt by many millions, but rather because it is somewhat dull to read since all the meaty bits, the scandals and, well, more scandals have already been exposed in its tsunami of reviews. It is held together by padding, and the padding is generally not of the same gripping stuff, which shows that the book has clearly been hastily written and proofread. My favorite blooper appears at the top of page 127 which reads, “Bannon was making his first official public appearance at the Trump presidency, and his retinue…” I am really hoping there was a missing l there. But then, given the rest of the book, perhaps not.

My other book read so far in 2018 is infinitely more beautiful and proofread. It is Winter Birds by leading bird artist and illustrator Lars Jonsson. The book is a winter journal largely based on observations from his Swedish homeland even more specifically, his Swedish garden “and explores the beauty of the birds that surround him during the Swedish winter months.” I bought my copy from a real bookshop so much better than an Amazon package dumped on the doorstep back in London and wallowed in it. The cover sports a stunning image of a pair of Bullfinches foraging through snow-decked brambles. The male is so spectacular thickset, with the bull-neck of his name and with grey, black and white upperparts offset by a deep rose pink breast. The female lacks the rose pink, but Jonsson argues she is even more attractive: “The pastel-like buff-brown of the belly reminds me of a colour chart for warm brown lipstick or eye shadow,” he writes and he waxes on lyrically, but it is not for me to expand here as the Bullfinch has never been recorded in Egypt and I do not want to tease.

What I was hoping for was a chapter on the Great Grey Shrike, a bird I have long associated with winter in England, where it is a rare winter visitor, let alone Sweden where it breeds. Sadly, there is just one reference to it buried in the introduction with a tiny vignette portrait in the margin, although Jonsson’s art is so breathtaking even a vignette becomes a masterpiece.

No, I had to wait until I got back to Egypt for my Great Grey Shrike fix. In the gardens of my workplace it is a fixture, a yearlong resident and soon to breed. In some ways, it is not unlike the Bullfinch, being grey and black and white above, but it is a larger, longer and slimmer bird, long tailed and with a hook at the end of the dark bill that announces it as a predator. Sometimes referred to as the Butcherbird, it preys on large insects, geckos, eggs, nestlings and the like. In times of plenty, it impales excess prey on the thorns of acacias. These rather gruesome stores for leaner times are known as larders, but the shrike is a modern bird; in a place where acacias are rather passé, it will happily substitute barbed wire.

Perhaps the defining feature of the Great Grey Shrike a common bird over much of Egypt’s agricultural areas is the black mask that runs through the eye, a bandit mask if you like. It shares this feature with all the other shrike species passing through Egypt in spring: the Red-backed Shrike, the Woodchat Shrike, the Lesser Grey Shrike, the Isabelline Shrike and of course, the Masked Shrike. Look out for them all in the coming weeks. They are bold birds often perching in the open. Wadi Degla seems good for the Masked Shrike and I found a female Red-backed Shrike last year at the Gezira Club.

Bandit masks are found elsewhere in the animal kingdom and unsurprisingly so. The eye is a peculiarly important organ for many species and a very vulnerable one, but a sweep of black across the face can effectively obscure it from unwanted predatory attention. Perhaps the best example is the Common Raccoon from the Americas, though here in the mountains of Sinai and more rarely across the North Coast is a mouse-like rodent called the Middle Eastern Dormouse or Asian Garden Dormouse. It is about 13 centimeters long with a tail of similar length buffy grey above, whitish below and with much of the tail, not the base, bushy and black often with a white tip. The throat is white and there is a black mask through the eyes, that bandit mask once more.

In the Red Sea, one of the most visible groups of fish are the butterflyfishes. Most are between 10 and 20 centimeters long, though the Lined Butterfly fish reaches almost 30 centimeters. All are rather disc-like from the side, often with a slender snout for poking noisily amongst the coral for food particles. Most are boldly patterned, especially in yellows and blacks; almost all have that black bandit mask through the eye. In the Lined, Blackback, Chevron, Threadfin and Striped Butterflyfishes, this is the conventional single black band. Indeed, the Striped Butterflyfish is sometimes called the Raccoon Butterflyfish. However, the Exquisite Butterflyfish has a double band; in the Masked Butterfly fish, the band is reduced to a deep blue patch around the eye and in the Orangeface Butterflyfish, rare in the Egyptian Red Sea where I have only seen it once, the whole face is dark save for a lovely orange dark. In many of those species described, the tail end is similarly patterned or marked. Any predator approaching a butterflyfish will be unsure which end is the front end or which end to attack and at which direction the butterflyfish will try to make its escape.

This strategy is used in other fish species too. Among the wrasses, a large and diverse group of fish found in all Egyptian waters but at their most prolific in the Red Sea, the Cleaner Wrasse and the Fourline Wrasse both are patterned with longitudinal black stripes that run through the eye, again obscuring it. The juvenile Dusky Wrasse, diminutive at just over three centimeters, takes this a step further. It shares the striped pattern, but on the rear of the dorsal fin, there is a very prominent ocellus, a false eye. In the adult, some 11 centimeters long, the pattern is lost but the eyespot is retained bigger and bolder than the actual eye with the intent to fool predators.

Perhaps the most famed example of the false eye is that of the Common Peafowl or peacock. Known for its stunning beauty all resplendent in gleamingly iridescent blues and greens, the male sports a long train of feathers, not actually its tail, that it can erect in a huge fan decorated with hundreds of ocelli by which it beguiles its potential mate. I was reminded of this when reading a bizarre story from Newark Airport in the United States. Apparently, people are now allowed to take animals on planes with them if they are therapeutic and help calm nervous fliers. For the most part, these are cats and dogs. However, an artist from New York’s Brooklyn was banned from taking her “emotional-support peacock” on board a plane as it did not meet the guidelines of United Airlines due to its “weight and size.” Pictures of the peacock ostentatiously perched on a baggage scanner went viral. His name was Dexter and he was a rescue peacock.

A peacock with full train approaches two meters in length. Perhaps next time, the artist should take an emotional support juvenile Dusky Wrasse.

Richard Hoath is a Senior Instructor at AUC’s Department of Rhetoric and Composition. He has published extensively about Egypt’s wildlife and fauna.

Comments

Leave a Comment