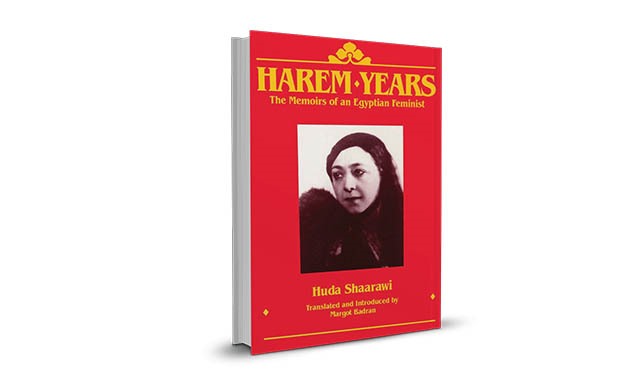

photo by Egypt Today

Pioneering Egyptian feminist Huda Shaarawi (1879-1947) chronicles much of her early life in the memoir "The Harem Years", portraying the limited role women played behind wooden lattice screens where they could look outward without being seen.

Shaarawi spent her childhood growing up in the segregated world she calls harem before she was married off to her cousin at the age of 13, and they separated merely months thereafter when she learned he was expecting a child from a slave girl.

Many of the female characters in her life, fellow members of the last generation growing up in those confines, led similarly unhappy private lives. A family friend, Atiyya Saqqaf, suffered “grief and desperation... that [undermined] her health” as her unfaithful husband took on marriages so numerous “he couldn’t count them, nor did he know the number of children he had.”

Shaarawi’s mother, a woman of Circassian descent, is described as melancholic, often carrying a profound sadness. Shaarawi herself is betrothed against her will to the relative referred to as “lord and master of all,” despite her being “deeply troubled by the idea of marrying [her cousin] whom [she] had always regarded as a father and family member deserving [her] fear and respect.”

Rigid gender norms characteristic of the turn of the 19th century into the 20th are clear in almost every line of Shaarawi’s narrative, where she grows from a somewhat passive woman often forbidden by her husband from visiting friends or other relatives, to a nationalist and a driving force of the flourishing feminist movement.

At the age of 44, she was elected as the president of the first Egyptian Feminist Union she co-founded in 1923, and activism became central to her later life.

Upon her return from attending an international feminist conference in Rome alongside Nabawiya Musa, the first Egyptian woman to earn a secondary school education, and Seiza Nabarawi, the younger daughter of a late friend of Shaarawi at the time, the pioneering feminists drew back the veil from their faces in a revolutionary act that signaled the end of the harem system.

Other women imitated, keeping only the veil on their heads and long black cloaks that were customary at the time. With this incident, the first layer unraveled of a culture of seclusion where women—particularly in wealthier circles—were entrapped in guarded walls and kept separated from men, covering their faces in the few instances where they left their homes. Interestingly enough, academic Margaret Badran notes in her introduction to the English-language translation of the memoir that peasant women had long uncovered their faces before unrelated visitors and strangers of the opposite sex as the practice was deemed unrelated to Islam.

Shaarawi’s memoirs end with the beginning of her activism. She returns to her husband in her 20s after a seven-year separation, and as the dual struggle for the liberation of Egypt and women heightens, their relationship grows stronger. “My attention was drawn from my private life to serving my country. The Egyptian national movement brought my husband and me closer to each other,” she writes. A man who had once clapped his hands in indication of his presence in the women’s quarters, who Shaarawi mentions as being “stern,” and one she had been “determined not to return to . . . whatever happened,” became her partner in fulfilling her newfound purpose.

Earlier in the memoirs, she muses over why her half-brother, Ismail, who she has a close and affectionate relationship with, is treated differently than she is, particularly given his illness at the time. His mother, Umm Kabira, then tells her, “But you are a girl and he is a boy . . . when you marry you will leave the house and honor your husband’s name, but he will perpetuate the name of his father and take over his house.”

While Shaarawi recounts this explanation was satisfactory at the time, her more egalitarian mindset and actions are clear with the foundation she sets in adulthood for a later generation of Egyptian feminists.

In the first year of the movement, the feminist union’s achievements included passing legislation to have a minimum marriage age set by law. By 1924, the first secondary school for girls opened in Shubra and soon, Egyptian women were permitted to obtain a postgraduate education. Shaarawi’s activities were also key to founding the Arab Feminist Union.

Shaarawi’s intellectual development is a critical aspect of her formative years, where she spent time learning music, languages, fine art and Arabic gram mar as a child and teenager. She played the piano long into the night as a catharsis to emotional pain and attended concerts at the Khedival Opera House.

She developed an interest in French literature, invested in deep friendships with peers she discusses cultural matters in the company of, and eventually played a role in organizing the first public lectures for women.

By the age of 9, Shaarawi had memorized the Quran, although she had been condescendingly told by one tutor that it wouldn’t be necessary for her to learn Arabic, given the limitations her gender entails.

Her journey is one of emancipation from social convention, and the beginning of this path is most apparent with her drive to establish the Intellectual Association of Egyptian Women in 1914. Initial members included Lebanese-Palestinian poet Mai Ziyada, founder of "Fatat al-Sharq" (The Young Woman of the East) magazine Labiba Hashim, and Luxembourgian women’s rights activist Marguerite Clement.

Although "The Harem Years" is an informative account of an iconic feminist actor whose positive influence was felt across the Arab world, the narrative is arguably weak and not particularly compelling.

Badran’s somewhat abridged translation from the original Arabic is loyal and truthful, but the detailed account of a time when women’s lives were more constrained and dull reads as tedious. "The Harem Years" is nonetheless an inspiring read of one leader’s journey to empowering others and paving the way for radical change.

Comments

Leave a Comment