As the gardens and landscaping mature, new fauna takes roost at AUC’s new campus

By Richard Hoath

It is June and the last days of Spring. So Spring has sprung and in the eye of this observer seems to have sprung with particular vigor. Last month — at the risk of reproducing myself, the point of Spring — I wrote of four probable new breeding bird species for the remote oasis of Siwa: Common Moorhen, Common Kestrel, Clamorous Reed Warbler and Blackbird. But you do not have to travel as far as Siwa to witness reproduction. That is happening much closer to the country’s capital at AUC’s New Campus in New Cairo.

The campus, my workplace, is huge at around 270 feddans; a significant portion of that is still desert awaiting further plans but treasured for the moment, at least by myself, as brown space. Then there is the academic campus itself, the buildings, offices, classrooms and halls that make a physical university a university. And a physical university is hugely important. I hold little truck with those who advocate distance learning or the trendy compromise of blended learning — the physical space is vital.

And then there are the gardens. These are extensive areas of greenery but a conservative greenery, greenery of species largely selected for water economy. Sadly the number of native species is limited but the familiar exotic species are there — mangos, lemons, limes, Date Palms and the like. And in a very special and secluded area there is a small clump of Papyrus. Now that is native to Egypt and, with the possible exception of the Date Palm, what plant could be more associated with Egypt’s history over the millennia?

I use these gardens not just as a place to rejuvenate my mental faculties but as an educational tool. I use them to talk to students about the importance of water and water budgets and how different plants cope in a hostile environment with little water. I have an Egyptology walk that emphasizes the plants and animals and discusses their relationship with Ancient Egypt. The Date Palm and Papyrus apart, the point is contradictory. Virtually none of the species so familiar to those who travel through modern Egypt —the maize, potatoes, tomatoes, sugar cane, bananas and so on — could possibly have been known to the Ancients as they were imported much later, many in post-Columbian times.

I also talk about the animals and birds but, being animals and birds, they are fickle. I know a plant is going to be there semester in, semester out, but the animal kingdom is far less predictable. But this Spring has been more reliable than previous Springs, more productive and seemingly more reproductive. Part of that may be my own observational bias but I think that a bigger part is that the gardens are maturing and developing, and a genuine new habitat has been created.

When I first visited the site that was to be AUC’s New Campus, it was literally desert and a desert ecosystem. The plants included many of the species still typical of the floor of Wadi Degla just a few kilometers to the south. I saw Mourning Wheatears, Hoopoe Larks and Desert Larks. I almost trod on a Cape Hare that erupted from beneath my feet, and the sand and gravel substrate was riddled with the tracks of gerbils and other rodents and of various lizard species.

The species have changed dramatically. But as the gardens and habitats have matured so new species have, for want of a better word, colonized. One of the first birds to arrive was the Common Bulbul. It is a largely featureless bird, 20cm long and decked out in somber browns and beiges with a distinctly darker head adorned by a slight crest. But as with many somber brown birds, not least the famous Nightingale (found here on migration but does not sing here), it is known by its voice rather than its visuals. The bulbul’s cascading, slightly chaotic musical babbling is a familiar sound over much of Egypt. In mid-May, I saw a pair with recently fledged young in the olive trees at AUC, the fledglings distinguished by their shorter tails and by the pale yellow gape of the bill.

Hoopoes, hudhuds, are also nesting. When I was a schoolboy in the suburbs of London, this was a bird of my dreams. Because it is a very rare visitor to the UK I had virtually no chance of finding d it there, but it epitomized everything that an exotic bird should be. It is boldly colored and patterned in black and white and cinnamon, has an extravagantly long and slender and down-curved bill, and has a flamboyant crest that is raised and lowered on instinct and, perhaps unscientifically, mood. In Egypt it is familiar but has never lost its allure. I have seen them ferrying prey, mostly substantial insects, to rooftop nest sites on the New Campus.

And of course there is the House Sparrow. Perhaps one of the most familiar birds in the world, it is often ignored or at best overlooked. But world-renowned wildlife artist and author and illustrator of Birds of Europe with North Africa and the Middle East Lars Jonsson is on record declaring that this is the bird he most likes to paint. He should know: he has painted every bird in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East! The House Sparrows’ scruffy nests of grass and fiber are all over.

Southern Gray Shrikes have also been doing what is expected in Spring. This handsome exercise in monochrome, all gray, black and white with a distinctive black facial mask is regularly seen in the gardens. Their nest has now been photographed by AUC student Menatallah Megahed.

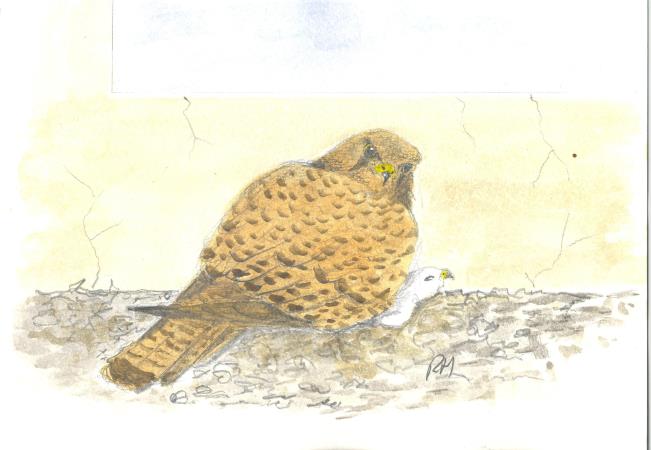

Which brings me to the last point. And the best. Menatallah is a biology student at AUC and was looking for a topic for her Senior Thesis. I had long suspected that Common Kestrels were breeding on campus and, in conjunction with Biology Professor Dr. Arthur Bos, suggested that this might be a potential study for such a thesis. There was one rather major problem. We had no solid evidence of breeding — a great many indications in the form of calls, and interactions between a potential breeding pair and potential nest sites tastefully marked by urine streaks — but nothing concrete.

After some time looking at potential sites we found the nest. A Common Kestrel nest is not a pretty sight — or indeed site. They go to no trouble whatsoever to build the neatly woven basket that is the popular conception of a nest. And, as is the case with most birds of prey, they are normally both faithful to their partner and to the nest site so that the latter becomes a build up of Common Kestrel detritus. The university administration was immediately informed of the nest location and straightaway closed the office outside which the kestrels were nesting. More than that, they gave permission for a computer camera to be installed at the nest site. The motion-triggered camera means that the birds’ activity can be monitored without disturbing the kestrels in any way. It is making for incredible viewing. Forget the Kardashians; if you want reality TV get a pair of kestrels!

As with any research project, the results of the observations must be studied and analyzed ahead of any formal publication. But as of the time of writing we have three chicks already hatched and being successfully reared by the parent birds. For me as a naturalist it is beyond fascinating, and Dr. Bos is no less enthralled by the research and scientific opportunities. But perhaps it is Menna who is the most excited of all. For an educator like me, to see a student so engaged and uplifted by the natural world is an enormous privilege. et

Comments

Leave a Comment