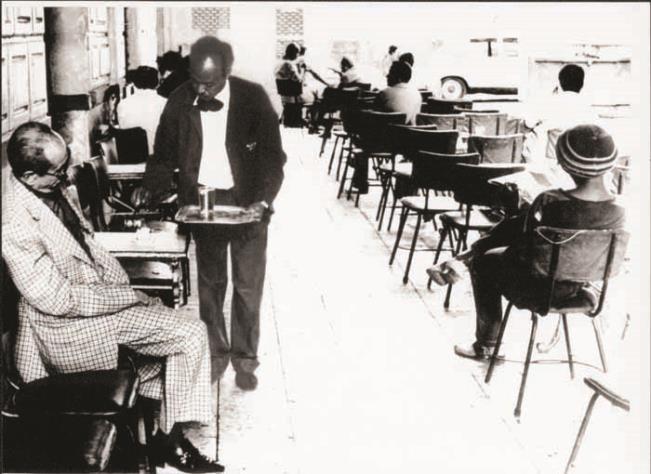

Documentary filmmaker Gamal Kassem’s film Café Riche tells the story of the landmark’s setting as a gathering point for Egypt’s famous thinkers

By Farah El Akkad

A blast of art hits the senses as you approach the door of Gamal Kassem’s Giza studio, which is stocked with exquisite antiques, posters, certificates and awards — a reflection of the documentary filmmaker’s passion. The layer of soft dust covering the old cameras, black and white photos and wooden antiques adds to the impression that this is a place where past and present meet.

Kassem, 58, graduated from the Cinema Institute in 1985 and started working as an assistant director, producing a number of short documentaries and films up until the production of his first documentary Café Riche in 2001. The documentary was nominated for an award at the Arab World Institute in Paris that same year. Café Riche was followed by other movies such as Bothayna in 2003, which portrays the life of an Egyptian peasant from Fayoum who creates a puppet show and theater in her village. Tabiaa Hayaa (Live Nature) nabbed first prize at the 2008 Ismailia International film Festival while The Nile’s Knight, released in 2011, depicts the life of Gamal El-Seguiny, the Egyptian sculptor who, frustrated by a lack of recognition from the state, threw all of his artwork into the Nile River. Between 2011 and 2013, Kassem directed more than four movies for the CCTV program “Faces from Africa,” including films about the Siwa Oasis, The Fisherman and his last documentary Ghalia, which presents the life of a lady who works as a cook to support her family.

But despite his years of success, it is Cafe Riche, the subject of his first project, that is closest to his heart. After a light conversation about the décor of the studio, Kassem invites me to have a seat with his welcoming smile as he begins reminiscing about the famous downtown cafe.

Located on Hoda Shaarawi Street in downtown Cairo, Cafe Riche was built by Austrian businessman Bernard Stenberg in 1914 and later sold to Greek businessman Michael Politis in 1916. Politis renovated the café and it soon became one of Cairo’s most popular spots. In the 1960s, Café Riche came under the ownership of an Egyptian Saedi named Abd El Malak Khalil who has been managing the place ever since.

Kassem chose Café Riche as the subject of his first documentary because of the significant role it played in the life of Egypt’s most renowned public cultural figures such as Youssef Idris, Naguib Mahfouz and Youssef Wahby. “The popularity of Café Riche rose after the 1919 Revolution, a movement that involved the ascent of many middle-class public and political figures in society, such as Saad Zaghloul. Between the years 1919 and the early 1940s, Café Riche was a hotspot for many famous poets and writers such as Ahmed Ramy and Tawfik El-Hakim.

“Cafés such as Riche were the type of places people would go to discuss and talk about the political events of the time,” Kassem recounts. The filmmaker explains, however, that in earlier years Café Riche was nothing more than a popular place where trendy people met to socialize, have a drink and listen to the tunes of Om Kalthoum and Sayed Darwish. After the 1919 Revolution, the atmosphere of the café changed dramatically, becoming the haunt of politicians and journalists.

Kassem’s film seeks to convey the message that, unlike other unique cafes such as Al-Borsa or Om Kalthoum’s that belonged to a particular social or political class, Café Riche presented a venue for Egyptians of different social and political backgrounds and professions. “It brought together politicians, along with writers, composers, musicians, artists, doctors and engineers,” explains Kassem.

The popular haunt also symbolized Egyptian society’s will and ability to always create “a voice” and a place to freely express their thoughts and opinions, no matter how the law might oppress them or their freedom of expression. “The Egyptian people were always able to create their own forum, Riche was more like an informal people’s assembly,” Kassem says. Along with the political and historical value of the place, and with many public figures calling Café Riche their “home,” Kassem says “it was a place where opinions were not underestimated or unwelcomed, [as] it was the place for all opinions, no matter how different from each other. The atmosphere of Egyptians who sat in Riche presented a sense of unity and goodwill, qualities we seem to lack nowadays.”

When asked what he liked most about Café Riche, Kassem recalls a quote by the chef of the café who would call the old Egyptian actor Estefan Rosti, who used to frequent the place, Estefan “Rosto.” The chef’s twist to his name mimicked the kitchen jargon he was used to,” says Kassem. “These little banters are what a documentary film is about.”

Since the 2011 uprising, Cafe Riche has become popular once more with revolutionaries and leading cultural figures like writer Gamal El-Ghitany, renewing the pertinence of Kassem’s movie a decade earlier. Revisiting Café Riche, viewers find themselves once again at a crossroads between past, present and future, drinking in the value of a place that represents Egyptian thinkers and where they expressed their thoughts, hopes and dreams for a better society and a better Egypt.

Comments

Leave a Comment